By: Ioannis Katsoulakis

«To err is human but to make the same mistake twice is not a sign of wisdom». This is a well-known saying from ancient Greek dramatist Euripides which, in a way, acknowledges that mistake-making is at the core of the learning process but, at the same time, individuals shall be able to learn fast even after one mistake only. What a combination of the two approaches that we will discuss in this essay!

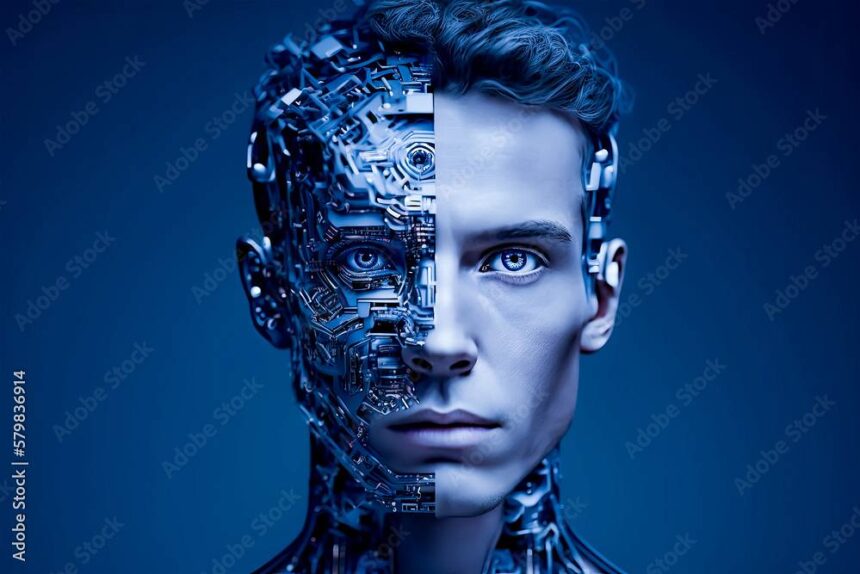

Since its inception at the Dartmouth Conference in 1956, Artificial Intelligence (AI) is a field generating excitement and hype from one side while raising several ethical and regulatory concerns from the other. From its very first days, AI researchers have been debating whether the best way to develop intelligent machines is by mimicking the human brain or by designing systems that are entirely independent and follow their own, novel approaches. This is not only a technical question but, even more, a philosophical one dealing with the future of humanity overall.

It is true that the human brain, with its ability to execute between 1013 and 1016 operations per second, is the only form of general intelligence we know, making it an obvious, natural model to study. Nature, though, may not always provide the optimal design, with machines potentially being an alternative and more efficient option to achieve intelligence as Demis Hassabis, Yann LeCun, and Gary Marcus support in their work, albeit with different levels of certainty and through different paths of implementation.

From the one side, having the AI research based on biology is justified by the fact that brain is humanity’s only working proof that general intelligence is possible thus, several researchers argue that neuroscience shall be our guide for the AI research. Many breakthroughs in AI such as artificial neural networks loosely modelled between brain neurons, are rooted in biology. Even though these models are relatively simple when compared to real brains, they can still be used as a base for learning from human systems. In addition, biology offers an understanding on how qualitative observations and perceptions can lead to fast decision-making through a complex-thinking process. For example, human beings can learn from a limited number of observations, generalize fast through complex brain processing of quantitative and qualitative inputs and reach a conclusion that is valid in most cases, something that AI can not do well so far unless large sets with thousands or millions of data are used. Biologic inspiration also carries the promise to make the machines more connected to people given that human-like thinking and reasoning may make the AI systems more trustworthy, relatable and, as the logic goes, more ethically acceptable.

At the same time though, biology-based AI research is facing some justified scepticism. Many scientists point out that the operation of the human brain is not even closely understood yet. With 86 billion neurons and at least 100 trillion synaptic connections operating through complex electrical and chemical processes, reverse-engineering the brain might be too complex to achieve. And even if achieved, it is doubtful that we will be able to reproduce its operation through silicon-based hardware and existing software-processing capabilities. Another limitation is that the brain evolution through the constraints of biology and its reliance on slow chemical signaling as well as the need to balance survival priorities like hunger or fear has an impact on its decision-making process that is not affecting the machines.

On the other hand, there are scientists who believe that although biological intelligence may be good enough for survival, it is neither efficient nor optimal. LeCun, for example, lays out his vision for autonomous intelligent machines that learn and reason in ways that are very different from the human brain leveraging the strengths and enormous processing capabilities of modern computation. For instance, while birds fly by flapping their wings, this is not the case with airplanes that use a more efficient, engineering-based model. Similarly, AI shall achieve new levels not by mimicking something that already exists (the brain) but rather by using machine learning and computer programming to educate itself from a limited number of examples extrapolated in a non-linear way to predict real world outcomes. Furthermore, human brains are more setup to survive in nature and to show empathy or practice social interactions rather than to solve complex numerical problems like the optimization of global supply chains, the simulation of climate changes, or the processing of the 150 zettabytes of data generated in 2024 which are projected to double every three years.

Still though these scientists do not completely dismiss biological intelligence as an area to leverage, although they insist that the future lies in innovation and out-of-the-box experiments. Deep learning provides such an example which, although inspired by biology and the operation of the neurons, works very differently by using mathematical operations and algorithms while leveraging computer capacity to process massive amounts of data. After all, human brain can learn from very few examples even only one, excel in general intelligence and abstract situations while continuing this educational journey throughout someone’s life while AI usually covers tasks defined more narrowly, require lengthy trial-and-error processes for being executed in a robust way, and their successful implementation is dependent on the analytical experience gathered during the learning horizon only.

As it seems until now, putting knowledge into practice with purely independent and novel AI approaches is hard to work without leveraging some of the characteristics of the biological intelligence. In that context, many scientists including Gary Marcus, argue that neither pure biologic mimicking nor totally independent approaches can deliver general intelligence and criticize deep learning for being highly dependent on massive loads of data while, at the same time, struggles with reasoning, causality and common sense. They call for combining symbolic reasoning, an approach linked to logic and representation, with learning methods based on statistics and neural networks so that robust intelligence can be delivered consistently and not in an unpredictable fashion. Such a perspective also highlights the importance of humility in AI research given that this is a rather new field with no guarantee which path will eventually succeed thus bets shall be cautiously split.

Reading through the different views, it seems quite clear that the choice between mimicking the human brain and pursuing purely independent intelligence shall not be one-way. Each path has its own advantages and contributes to valuable insights but, at the same time, carries some limitations. Biological intelligence is a rich source of ideas and examples that are often abstract in nature, but it is more complex to model and not always efficient to process as, in many cases, is based on limited number of observations. On the other hand, independent approaches free us from biological-intelligence constraints but are positioned away from the qualities that make decision-making flexible and quickly adaptable. As a result, my proposal is to proceed with a hybrid strategy where neuroscience will lead the design of cognitive mechanisms, memory structures and perception systems while leveraging computer science and applied math to invent new, algorithm-based architectures that go beyond biology.

In the end, the question of whether Artificial Intelligence shall mimic biological intelligence or pursue its own independent path is not just about engineering, it is even more a question of identity and vision. A question whose answer may define the very future of my generation and the generations to come. Yet Euripides can serve us as a guide for conclusion. True wisdom may be maximized by leveraging both options, taking inspiration from the brain but daring to invent beyond it!